Drum Transcriptions, Music

An introduction to Max Roach’s influence on jazz drumming

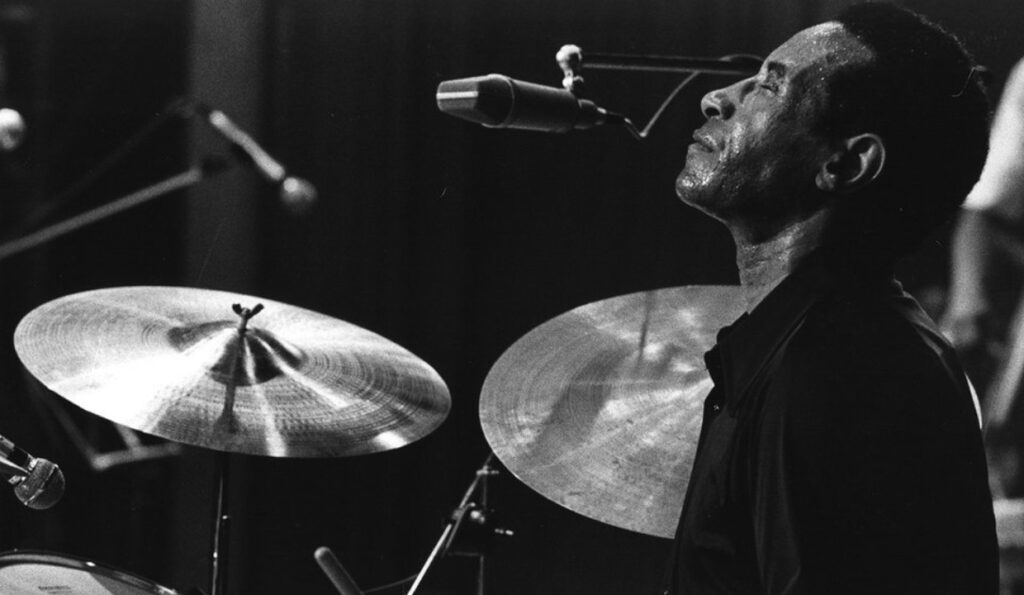

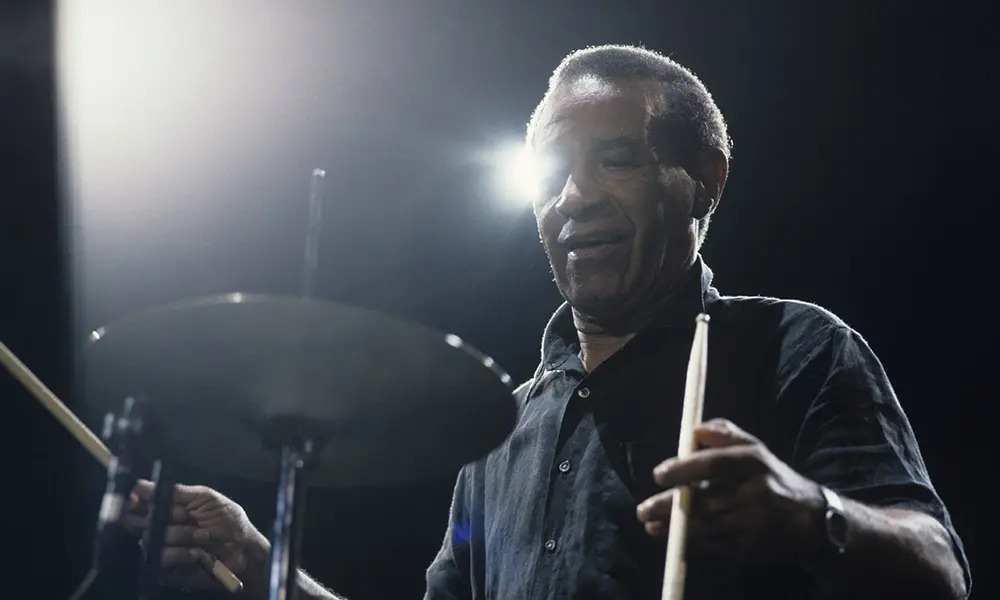

To complete my bachelor’s degree in jazz drumming, I took the opportunity to take a closer look at the music that has fascinated me for years. Throughout the years that I studied jazz drums performance at the LUCA | School Of Arts in Belgium, the jazz albums of Clifford Brown & Max Roach formed a heavy base in my personal jazz story. These albums are typical Hardbop-style with many remnants of the Bebop style. Max Roach and Clifford Brown only had the chance to work together for a few years, but those years were pretty successful.

In these four posts, located in the Drum Transcription section, I analysed four transcriptions of jazz drum solos played by Max Roach and their relation to the melody of the performed jazz standard. I examined these solos at a macroscopic level to look at the structure and then took different parts of each solo and placed them directly opposite the melody to find a relation between them. I did not analyse the entire solos. However, I think it forms an excellent base for further exploration. Additionally, in this post, I will dive a little deeper into the background of Max Roach and see how Max Roach became the player he is and how he influenced future generations.

An introduction to jazz drum solos.

Drum solos on jazz standards are inextricably linked to their performers and differ significantly between drummers. What Max Roach plays in his solos is an entirely personal vision and interpretation of the song performed. A different drummer with another background, experience and influence will approach and interpret the same music differently. As a drummer myself, it is incredibly fascinating to study these elements and investigate who the person playing the solo is. Moreover, where does his style of playing come from, and what influence does he exert on future generations? Putting the performer in time and space assigns an extra dimension to understanding the solo that has been played, and it enriches own knowledge and performance.

Who is Max Roach?

Max Roach, or in full, Maxwell Lemuel Roach, was an American jazz drummer who lived from January 1924 to August 2007. Although drumming was his most significant and well-known activity, Roach was also involved in music composition. His early training also ensured he was acquainted with the entire percussion instrumentation. Max Roach was born in the Newland Township at Pasquotank County in North Carolina. There is some controversy about his date of birth. While his birth certificate tells us he was born on January 10, his family claims he was born on January 8.

When Max Roach was four years old, he moved to Brooklyn in New York with his family. He had to deal with musical jitters early as his mother was a gospel singer. Max himself started playing the flugelhorn and soon ended up playing in various brass bands. Eventually, he switched from flugelhorn to drums and quickly got in touch with multiple gospel bands through his mother. Later in his life, as a student at the Boys High School in Brooklyn, he was asked to join the Duke Ellington Orchestra as a temporary replacement for Sonny Greer. As the replacement drummer, he plays several concerts with the orchestra in the Paramount Theatre.

Once Max reaches the age of 18, he moves into and around the jazz clubs of 52nd street and 78th street and enters the local jazz scene. Playing in the local surroundings is soon followed by his first professional recording. The recording took place in December 1943 as the drummer for Coleman Hawkins. Not much later, performances and recordings followed with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell and Miles Davis.

Max Roach expands his musical horizons.

In 1950 Max Roach decided to broaden his musical horizons further and studied classical percussion at the Manhattan School Of Music. After a three-year training, he obtained a bachelor’s degree in music. In 1952 he also started his label Debut Records with the bassist Charles Mingus. On May 15, 1953, the so-called Greatest Concert Ever, also known as Jazz at Massey Hall, was released on this label. This recording includes Max Roach, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell.

In 1954 Roach started a quintet with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the additions of Harold Land on tenor sax, George Morrow as bass player and Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell) on piano. Though short-lived due to the untimely deaths of Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, the group released an example of refined Hard bop playing along the lines of Art Blakey and Horace Silver in just a few years. Towards the end of the fifties, we see Roach playing with jazz singer Dinah Washington.

Further Career

In the 60s and 70s, Roach mainly develops his albums, including We-Insist! and Money jungle. In this period, we also find the start of his percussion orchestra, M’Boom. However, from the early 1980s, Max expanded further and started playing solo concerts. He proves with these concerts that he can fill an entire show using just multi-percussion setups. Max also puts together several bands and is not deterred by using less obvious line-ups. What follows are further experiments in his musical repertoire. The experiments range from free improvisation to writing music for theatre performances.

Eventually, Max Roach comes back to his roots and his classical training. He writes and performs works with classical orchestras and returns to the gospel world. He does this not only as a performer but also as a composer. This trend seems to be interrupted by appearing in hip-hop concerts. This includes performances with Fab Five Freddy and The New York Break Dancers.

The influence of Max Roach.

Max Roach, together with jazz drummer colleague Kenny Clarke, is seen as one of the founders of the bebop drumming style. In the 1940s, they devised a new concept in musical playing on the drum set. The beat-by-beat playing moves from a heavy bass drum pulse to a standard light jazz pattern on the ride cymbal. As a result, they create a flowing rhythmic pattern on which a soloist can solo with space and freedom. In addition, this pattern also provides independence for the drummer himself.

Instead of just keeping the tempo, the drummer now gets the chance to provide different accents on the snare drum, the bass drum and possibly other components within the drum kit. A logical consequence of this switch is the drummer’s involvement in a song’s melody. Because accents and interaction offer more possibilities than before, the drum set takes on a greater expressive and expressive role. It was possible to include parts of the melody in the drumming. The new playing style allowed Max Roach to switch from one dynamic rhythmic figure to another using a simple pattern. In other words, it allowed changing feelings and colours and surprise rhythmically.

Jazz drumming here reaches a stage where the role of metronome disappears, and the drummer becomes co-responsible for making music. Nowadays, jazz drumming has completely adapted to this style. But it was a real revolution in the 1940s. After the release of Max Roach’s recordings with Charlie Parker in 1945, many drummers were perplexed by the possibilities.

Stay in the loop!

My website has multiple ways to keep in the loop with music and travel-related updates. Make sure to follow my Instagram and Facebook pages to get the latest content on your socials. To get the updates in your mailbox, subscribe to the newsletter. I will post plenty of free drum lessons and other music and drum-related advice on this website in the future! Check out the drum transcriptions and analysis if you haven’t already. We can’t build this platform without our readers, so we thank you for your continued support. Stay tuned for many more to come!